2. Product Physiology

What studying Exercise Science taught me about building digital products.

My educational background isn’t in Computer Science or Graphic Design. I studied Exercise and Sports Science. I lettered as a D1 athlete. My first serious frameworks weren’t roadmaps or sprint plans—they were training regimens, playbooks, and route charts. A foundation in physiology and performance has shaped my perspective on product delivery. How?

Well, like the human body, as products grow, they become more complex. As complexity is introduced to the system, there is more alignment required. When a stressor is induced, the team sees how the system performs. Their takeaway creates more tweaks and changes to the product plan to ensure they get to where they want to be, whether that is in revenue, performance, or stability.

Maybe a quick story will connect the dots. Recently, I strained my Posterior Inferior Serratus muscle in my mid-back. This muscle connects the spine to the ribs, and though it is a small muscle, when it is hurt, the entire body is affected.

The serratus is a small muscle with a big job in the stabilization of the upper torso. Some of the pain created by the muscle pull included: rotation of the torso, extension of the hips, raising of the legs, hiccuping, and exhaling from the lungs.

Getting a massage on the muscle, to help recovery, was like getting stabbed between the ribs—painful. Recovery came over time, as I stretched, massaged, worked on mobilization of the entire back, obliques, glutes, and abdominals.

I couldn’t just work that muscle to recover. I had to work the entire system.

When building complex systems to support a simple, intuitive customer-facing experience, we often forget the interplay required in the system when something goes wrong or is compromised. The front-end experience design may have to change to fix the issue, but that is only the aesthetics… Many times, what the customer might see as simple changes has a cascading effect on the teams supporting the infrastructure of the system.

I’ve been through a couple of different security breaches in my time delivering products. Anyone in technology can attest, it’s not if, it’s when. The bad guys are always building tools, automations, tactics, workarounds, and scams to get into the systems that store transactions, PII (Personal Identifiable Information), and other sensitive proprietary data. Teams generally respond in two ways:

A toxic and dysfunctional team will first begin to shift blame, talk shit, and peacock on their soapbox, “I told you we needed to focus on security.” “I always have to clean up the messes (insert team name) produces, if only they would have discussed this with us.”

A healthy team will start asking questions, open a video war room, get all hands on deck, and work through the issues methodically (but with urgency). Learning will come after the resolution is deployed, in a post-mortem or incident report.

A healthy team learns how to get better from these types of incidents, creating processes or new features and systems to prevent future events. Individuals on toxic teams learn how to CYA (cover your ass), to not find themselves in the cross hairs of executives looking to execute blame.

Just like body maintenance for performance. A healthy team is always asking itself, “How can we be better tomorrow?”

Is our diet balanced, healthy, and up-to-date with the latest in best practices?

Does our support team have all the information to respond to issues and setbacks?

Do we need to change our delivery strategy to include another team’s input or oversight

The questions a healthy team asks themselves are not to find blame, but to find better.

Better people.

Better processes.

Better testing plans.

Better time for recovery.

We can say more about responding to adversity, but maybe the last comment is a simple one—teams can’t let the muscle that drives innovation become myopically focused on progress, cross-training on incident response, customer support, and resolving technical debt has to be prioritized. A healthy team understands its strengths, weaknesses, competencies, and growth opportunities.

As a leader, you need to make time for a holistic view on product delivery; it can’t be a second-class citizen; it needs attention and prioritization. Otherwise, your potential for a top performance will be out of reach.

Let’s transition to training for performance.

We’ve been through the fire, recovered from the injury, and are beginning to track, holistically, toward consistent performance. How do we work? Is it pedal to the metal? Full gassers after every practice? No. Please don’t do that. In training, this leads to burnout, stress fractures, and disgruntled teammates.

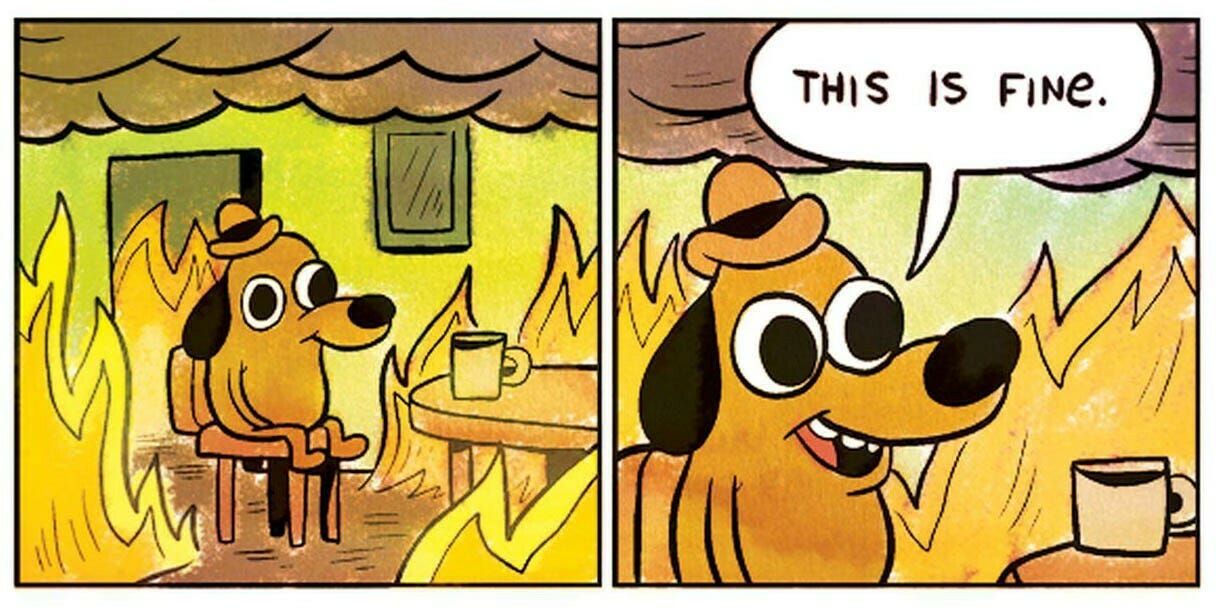

Many leaders have the poster, “Life is a marathon,” framed in their conference rooms or offices… while the workers have the “This is fine" cartoon taped to their cubicle wall. The dichotomy is telling. If this was an Agile Manifesto, not a Product Manifesto, I would go on a diatribe about Waterfall versus Agile Project Managment practices and how the Waterfall process lends itself to this type of outcome, where the executive team drives the delivery team at the same pace and level of urgency for what is planned to be a 6-month project… that usually lasts 3-4 years.

Think I’m exaggerating? I am not. I’ve been a part of projects like this, and the disconnect between management and delivery is so vast, it’s surprising anything ever does cross the finish line. In projects like these, your top performers leave for greener grass, and many of your average performers quietly quit or, at the very least, significantly reduce their productivity, to the point that asking for any feature delivery is automatically a 6-10 week scope.

Maybe life shouldn’t be a marathon?

Any good coach will tell you: a marathon is a grueling event. Whether you’re chasing a personal best or just hoping to finish without collapsing, it’s going to test every system in your body. If life were a marathon, most of us would be dead by 37. But training for one? That’s a different story. That’s where things get interesting. Training has rhythm. Variation. Recovery. Good training is responsive, adaptive to your needs to the goal. In that sense, a good work life shouldn’t feel like a never-ending race. It should feel like training for something worth doing. Race days come once or twice a year when you launch the app, deliver the product, or give that pivotal presentation. You work to perform your best in the situations that arise.

I learned this the hard way. I was 35, working long hours, stuck behind a desk most of the day, coming home to three kids under five (two of them twins), fetching my dinner after 8 pm from the fridge wrapped in foil, ready to be reheated. I saw a photo of myself playing with my kids before their bedtime and didn’t recognize the person I saw—tired, swollen, and completely out of sync with the life I was supposedly building. I needed to change. So I called a friend who was a great runner and coach. I gave him the usual spiel—“I’m overweight, out of shape, and stressed.” He nodded, then told me flat-out: “That’s not a goal.” So I gave him one. “I want to run a half-marathon.” He smiled and said, “Let’s start with three miles.”

Over the next few months, I built up to a baseline. No glory, no gimmicks—just steady, flexible training. When we finally sat down to plan out training for the Memorial Half-Marathon, he didn’t just give me a mileage chart or off-the-shelf training program. He built a rhythm. There were sprints and tempo runs, bike rides, swims, long slow Zone 2 runs, and rest days. He didn’t want me to just survive race day; he wanted me to become a runner. And I did. My body responded, and my psychology shifted from anxiety to anticipation.

I began to recognize what fueled a good long run (banana + peanut butter sandwich) and what ruined one (leftover curry). I adjusted gear, shifting to clothes that fit better and didn’t chafe!! I iced my shins and rolled the bottom of my foot on tennis balls. I did some evening yoga. I tracked recovery. I trained hard, but it was never just about surviving the day; it became more about building a body and mindset that could flex, fail, adapt, and improve.

When race day came—the OKC Memorial Half—I hit my goal: 1:58:18. Under 2 hours!! I was ecstatic and surprised that what stuck with me wasn’t the finish line.

It was the realization that life isn’t a marathon. But it could be a lot like training for one.

And the same is true for building digital products. Race day comes—launch day, pitch day, whatever it is—but most days are not that. Most days are for the work in front of you, the pace that makes sense, the changes that keep you distraction-free and forward-moving. You don’t build great products by pushing endlessly. You build them by training well. With rhythm. With range.

We can sometimes get lost in the metaphors and forget—product delivery is not a one-person race—it is a team sport! And teams have different positions, units, skillsets, and demands. You aren’t alone running on empty trails and a vacant track. You are training with others who have slightly different assignments, all meant to build a great product for your customers.

And we have to remember that a well-built product flexes, just like the members of the team. It learns. It gets stronger through feedback. It fails, adapts, and iterates. When marketing isn’t at war with product, and engineers aren’t burning out to meet arbitrary deadlines, when product is communicating the what & why, a team can slip into the zone, step into the flow, where work becomes fun, collaborative, and fulfilling. Yes. We can have meaningful experiences at work, in training, in practice. It isn’t just about the performance; we have to find a way to enjoy the work, the journey, the day-to-day grind of becoming the best you can be.

Life is a lot like training for a marathon.

And yes, training can be fun.

Next Up: Chapter 3. Build for Belonging.

Trusting your team to perform means more than just delegation. It means alignment around meaning, mission, and mutual respect. People don’t give their best work to systems that ignore them.

That’s where belonging comes in.